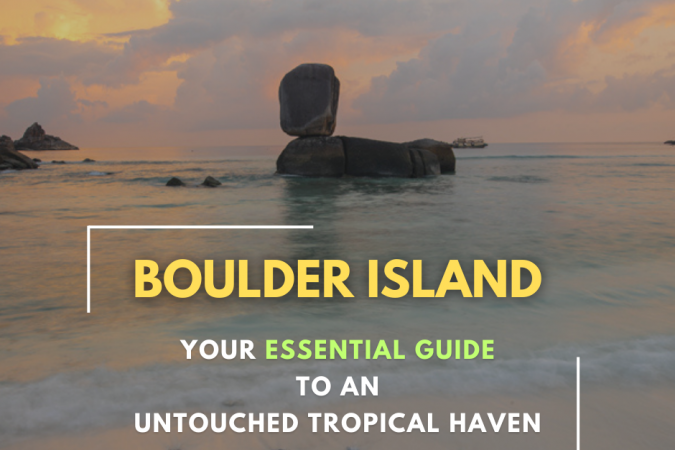

Isolation and inaccessibility have kept tourists away from the Mergui Archipelago, however new eco-sensitive developments may turn its islands into the ultimate escape.

By KEITH LYONS NOVEMBER 11, 2018 1:46 Asia Times

Few have heard of the Mergui Archipelago, and even fewer have managed to visit the 400km string of scattered islands in the Bay of Bengal’s Andaman Sea. Most of the 800 offshore islands are uninhabited, apart from a few seasonal settlements of the seafaring nomadic Moken, and some Burmese fishing villages.

The jungle-clad limestone and granite islands fall within the jurisdiction of Myanmar, though the island group, like the illegal fishers that operate in the warm waters, is no respecter of international boundaries, with some of the archipelago extending into southern Thailand.

The political sensitivities around this maritime border, and the lack of resources to manage cross-border smuggling, combined with a neglect by the Burmese generals during the five decades of the military junta, meant the region was strictly out-of-bounds for all Burmese. The only activity allowed was resource exploitation – tin mining, timber extraction and fishing – by cronies and military associates. Most of the raw materials were flogged off through grey markets to Thailand.

Myanmar’s recent moves this decade towards democracy and economic development in the country’s south has highlighted the region’s potential, and new infrastructure will connect it with neighboring Thailand, as well as with the former capital Yangon, some 1,000 kilometers away. The Mergui Archipelago has been identified as a possible jewel in Myanmar’s tourism crown, and a handful of islands were flagged for development by tourism authorities.

Regarded as the ‘last island paradise’ in Asia, the archipelago is now opening up to small-scale tourism. The first foreign visitors over the last two decades were divers aboard chartered liveaboards out of Phuket in Thailand, who came for the coveted dive spots teeming with manta rays and sharks, but were not allowed to stay on any of the islands.

The expense and need for permits and marine entry fees still present barriers to an invasion by tourist hordes, though the opportunity for island day-trips and a weekly arrival of a cruise ship from Malaysia suggest things are changing fast.

Lack of facilities, digital detox

Currently, the main challenges are the lack of tourist infrastructure and the difficulty in accessing both the region and the islands. However, it is the lack of facilities and the logistical difficulties which means those who do make it to the islands hold the bragging rights of being there first.

While tourism in the nearby Similan and Surin islands in Thailand is ‘developed’, the Mergui Archipelago’s remoteness means there is no mobile coverage, though it does mean world-weary visitors can have a digital detox.

The gateway port of Kawthaung at the southern-most point of Myanmar is more easily reached from the Thai town of Ranong, where noisy longtails ferry visitors across a wide river estuary to Myanmar, a country 30 minutes away, although several decades behind Thailand.

Flights from Yangon to Kawthaung are relatively expensive, around US$160-180 one way, while two budget airlines fly from Bangkok to Ranong for as little as US$30. Myanmar e-visas (US$50) obtained in advance are required for those wanting to explore the Mergui islands.

Apart from a five-star casino catering to Thai gamblers a short boat trip away from the mainland, the first accommodation in the archipelago, Myanmar Andaman Resort, has dropped its ‘eco’ label and now devotes its attention to day-visitors who disembark from a cruise ship twice a week during the season, which runs from October to May.

The first operator to enable anyone to explore the islands without the net worth to charter a boat was Moby Dick Tours, which runs island-hopping safaris aboard a converted junk Sea Gipsy, with open-air sleeping areas, and opportunities for snorkeling, kayaking and swimming.

In 2017 Moby Dick’s founder Bjorn Burchard established Boulder Bay Eco-Resort on an outer island, a largely self-sufficient rustic cabin resort suited to active guests and nature-lovers. The resort sponsors marine conservation efforts, including the restoration of coral reefs by the NGO Project Manaia, using discarded fishing cages to create new habitats among coral broken by dynamite fishing or dragging anchors.

Aware of the challenges ahead for Myanmar, the resort hosts marine biology students and teachers from the local university. “We want to empower locals to be involved in the future of this region,” he says. A campaigner against the use of disposable plastics, Burchard is also seeking to protect the island’s waters as a marine no-take zone to help replenish fish diversity.

Turtle hatchery, tent villas, treehouses

Another initiative which offers an example of sustainable, appropriate development is the Wa Ale Island Resort, located within the Lampi Marine National Park. The conservation-led ecotourism project first established a turtle hatchery on Wa Ale Island before the tent villas and treehouses were constructed using mainly recycled and repurposed materials.

“More than 40 sea turtle nests have been protected, saving an estimated 4,000 sea turtles,” says Benchmark Asia’s Christopher Kingsley. “Wa Ale Island Resort will allow travelers to access one of the most unspoiled areas in the world for the very first time. Our mission is to enable guests to experience the natural beauty of the archipelago in a way that encourages responsible and sustainable care for the environment.”

The Lampi Foundation, set up in parallel with the barefoot luxury resort, is working with the villages of the foraging Moken and Burmese fishers to prevent poaching, while improving healthcare and education among the few local inhabitants. Kingsley believes the habitat protection and community development model at Wa Ale could set a precedent for future tourism projects in the archipelago.

This month, the first guests set foot on the white sands of Wa Ale, signaling the start of a new era for the region which has long been pirated, plundered, and poached. Sunsets in the archipelago are stunning events witnessed by only a few, but this could be a new dawn for the mysterious islands.

Keith Lyons (keithlyons.net) is a New Zealand writer with a long interest in Myanmar. He contributed to ‘The Best of Myanmar: The Golden Land of Hidden Gems’ (KM, 2017), was editor and co-author of ‘Opening up Hidden Burma’ (Tenko Press, 2018), and is working on a book about the Mergui Archipelago with photographer David Van Driessche.