Regarded as one of the last untouched regions in Asia, Myaynmar’s isolated Mergui Archipelago is slowly opening up with new conservation-led tourism initiatives, as Keith Lyons discovers.

There are white soft-sand beaches on the islands of the Mergui Archipelago where no one has set foot. Largely uninhabited – and unknown – the archipelago’s 800 islands in the Andaman Sea, off the coast of southern Myanmar (Burma) and Thailand, are scattered across an area 100 times the size of the Bay of Islands.

In centuries past, these islands sheltered ships (and pirates) plying the Indian-Asian sea trade routes but in recent times no one could access this vast region. It was only in the late 1990s that the Burmese military first allowed foreigners in on expensive chartered live-aboard dive boats from Thailand. Those intrepid divers boasted about seagrass-grazing dugongs and the extensive coral reefs teeming with tropical fish, whale sharks, and migrating whales. There was talk of diving with manta rays, and a swim-through to a secret lagoon packed with docile nurse sharks.

As Myanmar moved towards democracy earlier this decade, tourism has slowly opened up. With lush evergreen forest cloaking the limestone and granite islands fringing coral reefs creating white-sand coves, and picture-perfect turquoise warm waters, there is something appealing about the island paradise. It is not just abundance and diversity of life on land and in the sea, but the absence of mass tourism holiday-maker hordes seen further south in Thailand.

Wa Ale Resort is located within the Lampi Marine National Park, established in 1996. Among the endangered species found in the park is the world’s smallest hoofed animal, the mouse deer, while one of the 250 bird species recorded is the Nicobar pigeon, a surviving relative of the dodo.

It was a landmark event when the first guests set foot on soft sand at the long sweeping beach at Wa Ale Resort (https://waaleresort.com) late last year. In 2016, long before the 11 luxury tented villas and two treehouses were erected, the resort worked with under-resourced government departments and the Wildlife Conservation Society (https://www.wcs.org) to protect and secure nesting sites for endangered sea turtles. Even though the resort is within a nationally protected area, previously nests were raided and the turtle eggs sold on the black market.

“The protecting of more than 40 nests is saving an estimated 4000 sea turtles“, says resort founder Christopher Kingsley of Benchmade Asia Myanmar.

“Biologists found that the leatherback turtles on the island were a species that have disappeared from the mainland. Now, at certain times, our guests will be able to watch these turtles on their nocturnal journeys between the sea and the dunes.”

Kingsley believes the “barefoot luxury” resort will enable access to one of the most unspoiled areas in the world.

“We want guests to experience the natural beauty of the archipelago in a way that encourages responsible and sustainable care for the environment,” he adds.

Buildings and walkways are made with wood recycled from old warehouses, monasteries, and boats, and he says strict guidelines included not cutting down large trees, not building on the coral, and no commercial laundry facilities.

More than 20% of resort profits go to a foundation which is protecting habitats and preventing poaching by Burmese fishers and foraging by the islands’ seafaring indigenous Moken people (known as sea gypsies), as well as assisting with healthcare and education in the settlements. The foundation’s pragmatic approach includes providing fuel to fishers so they do not fish inside the island’s ‘no-take’ zone.

Protecting, restoring, and educating

While the Mergui Archipelago is on the “tentative” list for World Heritage status because it has the least-degraded marine, mangrove, and lowland forest habitats in the Bay of Bengal, there’s an ugly legacy from plundering. Illegal trawling, the use of dynamite fishing, and over-fishing by clandestine Burmese and Thai fishers has depleted fish stocks and left gaping holes in the coral reef.

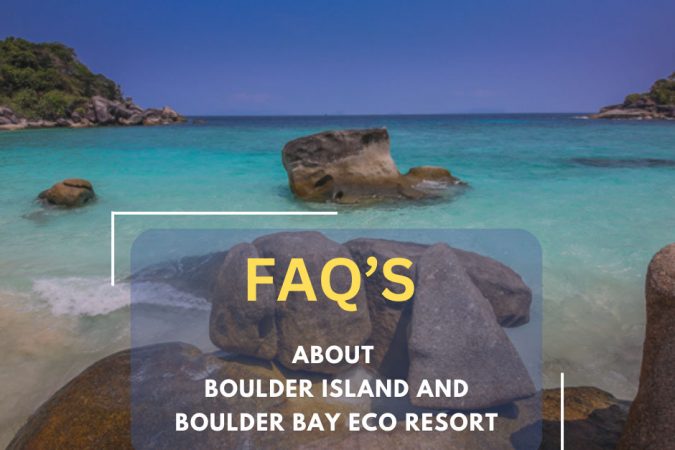

But there is hope. For example, on boulder, one of the most easterly outer islands in the archipelago, a unique partnership with European NGO Project Manaia (https://www.projectmanaia.at) is showing how conservation-led ecotourism works, and that habitat damage can be reversed.

Sponsored and supported over the last three years by the Boulder Bay Eco Resort (https://boulderasia.com), surveys have found a wide diversity of fish, invertebrates, and molluscs. Just off the resort’s main beach, branching plate and sponge corals provide a habitat for brilliantly banded surgeonfish, gliding angelfish, and coral-eating parrotfish. The health of the island’s coral gardens is indicated by the presence of the iconic clownfish (as featured in the movie Finding Nemo), which lives symbiotically among sea anemones.

In an innovative project, coral nurseries have been established on discarded ropes, and old abandoned fishing traps were repurposed to create new coral-growing environments in areas damaged by blast fishing and dragging anchors.

Local coral reefs have significance beyond their borders. When corals in nearby Thailand were severely bleached in 2010, polyps from Myanmar helped restore the marine ecosystem.

Researchers Matija Drakulic and Isabelle Ginisty are designing snorkelling trails, identification charts, and educational panels, as well as cleaning rubbish off the coral, and removing ghost fishing nets. Guests at Boulder Island can help with beach clean-ups, learn about the source of the rubbish – and what they can do about it.

With its minimal impact, solar generation, and natural material design, Boulder Bay Eco Resort could set the benchmark for other resort, according to New Zealand-born architect Richard Morris, co-founder of local bamboo design and construction company Pounamu (https://www.pounamu.com.mm).

“There is a lot of development presently proposed for the Mergui Archipelago which could not be considered sustainable, no matter how they try to package it. Sustainable tourism is a new concept for Myanmar”, he says.

Drawing inspiration from the success of New Zealand’s first marine reserve, Goat Island, the resort’s founder owner Bjorn Burchard wants all fishing prohibited from around the 135 hectare Boulder Island.

I’m pushing for a ‘no-take’ marine-protected zone, to increase fish stocks and bring back biodiversity so we see more fish stocks and bring back biodiversity so we see more fish abundance and larger fish”, he says.

“There is opportunity here for sensible, sustainable ecotourism. But also a danger that without proper guidelines and management it quickly becomes spoiled like Phuket.”

*Keith Lyons (keithlyons.net) is a New Zealand writer covering science, environment, and travel in Asia. The former Forest & Bird staffer contributed to The Best of Myanmar: The Golden Land of Hidden Gems (2017), and was co-author of Opening up Hidden Burma (2018). Keith is currently working on a book about the Mergui Archipelago.